BEHIND THE SCENES ON RUADH STAC MOR

A personal perspective by Bill Amos, Dundonnell Mountain Rescue Team Member

Dundonnell MRT covers a vast and remote area of approximately 2500 square miles. During rescues, we keep in touch with each other and our roadside base using handheld VHF radios. Maintaining communications presents a major problem because, just like your mobile phone, the signal is mainly line of sight. Our job in the 25 mile Challenge is to provide radio and safety cover over the whole route. We pass on the identification numbers of all participants to the GWC marshals so that each participant can be checked off as they pass through. We can also alert the next checkpoint about any participant who may require help and call in the helicopter if required. This requires radio links (or relays) to enable messages to be passed between checkpoints and back to the main Team base above Poolewe, and then to the organisers at the hall and finish line. In addition to the radio links at the GWC checkpoints, relay stations are located at high points to enable complete cover of the whole route. If you imagine the radio waves as straight wires, there is an unseen spider’s web above and beyond the GWC route. A “sweep”, once referred to as Sooty, follows the last walker along the entire route.

For myself and one other team member, the event starts on the Friday afternoon when, thanks to the co-operation of Letterewe Estate, the GWC Carnmore “soup kitchen” and ourselves go by Land Rover to the boathouse at Bad Bog and then by estate boat up the Fionn Loch to the jetty at Carnmore. Everyone helps to transfer the soup kitchen gear and tent to the bothy at Carnmore. We then head off up the Carnmore path with a tent, sleeping bags, evening meal, radios and other gear. At the cairn just after the path’s high point, we leave the GWC route, cross the river, pick up 6 litres of water and follow the stalker’s path south-east until it runs out on a flattish area, at about 2000ft. We then climb up over rough scree close to the line of crags that overlooks the highest section of the GWC route, cross the plateau and continue to the summit of Ruadh Stac Mor (the big red peak). Twenty feet along from the summit cairn there is a tiny patch of nearly flat ground with just a few stones near the surface and it is here that we pitch our tent. The back door is literally on the edge of the cliffs above Fuar Loch Mor which lies hidden from those on the GWC route and is about 1000ft below us. From our 3014ft vantage point we look down on the causeway between Dubh Loch and Fionn Loch and out to Poolewe. We have an amazing 360 degree panoramic view of the surrounding mountains.

Because of the height and location, this is an ideal location for the main relay; it is possible to keep in direct contact with most of the Dundonnell checkpoints, including the base station above Poolewe; Carnmore; the top of Gleann na Muice Beag zig-zags; Shenavall and the high point of the path from Corrie Hallie. We use a few stations to provide a link to those we cannot reach directly. Team members staying overnight at Shenavall pass back information about the level of the rivers in Strath na Sealga in the evening and again at six o’clock on the Saturday morning, when a decision is made about the safety of the crossings. Once the event is underway we can keep our Poolewe base up-to-date about the location of the walkers and runners as they pass between the checkpoints. In clear conditions we are able to watch who are doing the GWC as they pass along the high level path next to Maclean’s Loch, between checkpoints 3 and 4 far below us. Sometimes we have called in team members and/or the helicopter for incidents that we have seen but mostly we relay requests from the other stations for help or we answer questions about “missing” walkers. We have also welcomed astonished Munro baggers to this very remote and rugged peak with a cup of coffee and the offer of a bacon roll!

On most of the occasions that I have spent the night on Ruadh Stac Mor, there have been the expected difficulties on the way up, mainly rain, heat, sometimes sleet, wind and usually midges and sometimes a dodgy river crossing. The main problem is lugging a heavy sac up to the summit plateau through the rocks, scree and loose earth. However, sometimes simply reaching the summit has provided its own particular challenge.

Ascending from Carnmore in 1998, we looked down on to the Fionn Loch causeway which was almost under water. Every river was in spate and burns rushed over paths. When we turned off the GWC route at the top and only just managed to cross the river, we knew that if the rain kept up we would be unable to get back over and would have a very long walk out. We also knew that it was likely the 25 mile route would be ruled out and were prepared to consider a difficult and unpopular decision. Stuck in the clouds the following morning, we relayed the information that neither of the rivers at Shenavall could be crossed and that the causeway was now under water. The decision was reluctantly taken to use the alternative route and we were asked to relocate to the path junction at the Carnmore end of the Letterewe track. We informed base that it would take at least four hours to get there, so the helicopter was sent, which, after a few attempts, loomed out of the cloud, creeping up the hill in reverse a few feet from the ground. It picked us up and quickly dived down below cloud level.

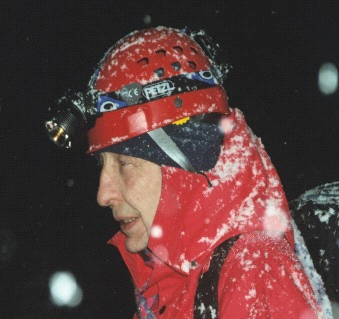

A few years ago, after a bumpy sail up Fionn Loch, Angus Mackie and myself set off up the Carnmore path with a strong wind (or in Culbokie speak “a good draught”) behind us, crossed the river at the top and after another kilometre emerged on the flat plain below the cliffs of Ruadh Stac Mor, and a “draught” that was now storm force. Plumes of water were rising up from Fuar Loch Mor, a hundred and fifty feet below and were soon soaking us as we stumbled on. We were in a whirlwind of wind, rain and loch spindrift, created by Ruadh Stac Mor, A’Mhaighdean across the loch, and the bealach between the two.

We were being swirled about in a virtual cauldron. After being blown over a few times, we agreed that getting anywhere near the summit that night was impossible. We headed North with the idea of camping lower down and ascending at first light in the lee of the mountain; but we were no longer in charge. As the wind speed increased we were blown north and downhill, over rivers, bogs and boulders until we were close to Maclean’s loch, opposite and at about the same height as the GWC checkpoint 3. Now in darkness, we struggled to erect the tent, but before we managed to get inside, a pole snapped. In mountain rescue terms, our personal safety was now our priority and we started on the long journey back towards Carnmore and a mobile phone signal, arriving back to a startled but welcoming “soup kitchen gang”. We swopped jobs with team members who were originally going to man our Carnmore checkpoint and they, plus others, set up a modified radio network; a slightly relocated “spider’s web”. The following morning, GWC participants faced a strong headwind but none were aware of anything being different from the previous years.

Events such as these heighten awareness of the dangers and problems of being in the mountains but they are only a small part of the experience and my memories are filled with the evenings and mornings of just being there. It is a privilege to sit beside the tent watching the sun setting over Loch Ewe, Fionn Loch in shadow, while we enjoy the last few minutes of the Alpenglow on the summit with a dram. Later, the lighthouses of the west flicker into life, followed by the twinkling ribbons of light in Stornoway and Achiltibuie; eastwards, a big yellow moon rises to cast a warm glow over the high mountains. After a warm day, we can expect to sense and then catch sight of a small herd of deer on the plateau below.

In the morning, the views over to Torridon and further afield form a backdrop to the dark outline of A’Mhaighdean (The Maiden), our near neighbour, which usually entices one of us to get up at six o’clock in the morning to pay the old girl a visit, on one occasion with an artist’s sketchpad. Sometimes we wake to a cold mist whilst those below enjoy the heat (and midges) of the morning; at other times it is we who float on our high top on a sea of moving cloud above the unseen Wilderness below. I have done this job at least twenty times and each trip is coloured by different incidents, events and the mood of the weather. We watch the sunlight and clouds play on the rocks, sometimes deep black on one side, with glistening crags and lochs elsewhere; hills and glens in a sea of drifting cloud, mountains rising above, catching the sun; the ever-present wind rippling the lochs and grass, waterfalls tumbling down A’Mhaighdean; the day or year changes and there are waves on Fionn Loch, and waterfalls are blown back uphill; all this can happen on the same day, over our 360 degree panorama. The interplay of the wilderness and weather combine to produce a different experience each time and leave memories that just have to be revisited. Who needs to climb all the Munros! I am drawn back each year as an old friend, a feeling I am sure I share with all those organise, help and take part in their own personal experience of “The Challenge”.

Author’s Note: since writing the original article, a chronic back problem means that I am no longer able to cart up a heavy sac of gear – but the job still gets done and those doing it now are, metaphorically at least, blown away by the experience.

Scotland360

I’m Angus Mackie, a professional photographer, based just north of Inverness on the beautiful Black Isle. I'm on the North Coast 500 and am well placed to discover most of the Highlands. The iconic scenery of Glen Affric and the Cairngorms are close by whilst many of the wild and dramatic locations on the west coast are within easy reach.

Mountains, landscapes, coastlines.... As a landscape and panoramic photographer, I enjoy exploring Scotland and its wild and remote places and have discovered some of the best photography locations in the Highlands over the last 35 years of living up here. With a broad and wide ranging knowledge of the Highlands, I still enjoy finding new locations and fresh perspectives for my photography. The use of natural light to capture stunning scenery at spectacular locations is very much a key factor for my photography.

I’m a qualified Summer Mountain Leader, a Sea Kayak Leader and a UKCC Level 2 Sea Kayaking coach, with many years experience of leading and guiding. I was also a longstanding member of Dundonnell Mountain Rescue Team.